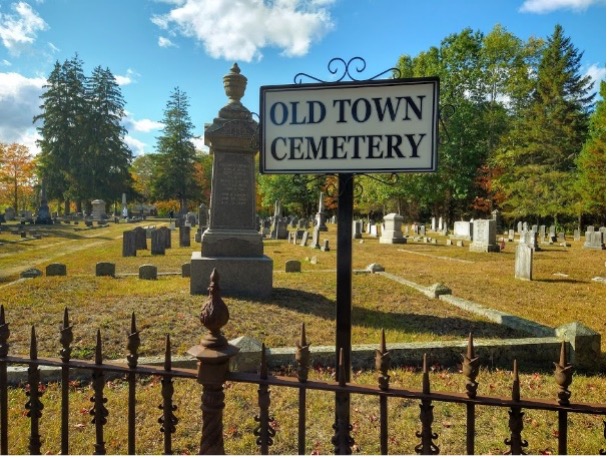

A walk through Rollinsford’s historic Old Town Cemetery reveals much about the town in the 18th and 19th centuries: its ethnic makeup, values, and beliefs; the impact of infant mortality in an era before modern medicine; the close bonds of kinship between families; and much more.

In the oldest section of the cemetery is the grave site of Colonel Thomas Wallingford. Colonel Wallingford was an important person in 18th century Somersworth (what is today Rollinsford). As his gravestone attests, he was colonel of a regiment and a judge of the superior court of the colony. He was also a benefactor to the town and gave the gift of a bell to the town’s meeting house.

On Sunday, August 4, 1771, Colonel Wallingford was at Captain Stoodley’s tavern in Portsmouth (perhaps on business or given the tense times, a political meeting) when he died suddenly. That same evening his body was brought back to Somersworth for burial, which took place two days later.

Most likely a large crowd of townspeople gathered in the cemetery for the funeral rites of such a prominent person. However, one less-than-honest member of the community instead used the funeral as an opportunity to commit a little larceny. Joseph Tate, the local schoolmaster, recorded in his diary:

During my wife and daughter’s absence, they being at Colonel Wallingford’s funeral, Love Roberts, Jr. climbed up the side of my house, into the chamber window. I saw him in the chamber. He made his escape by jumping out at the other window. My chest was broken open. I lost near 4 of old cheese, with some tea and coffee. Mr. James Roberts was sawing at the lower mill and saw him make his escape.

Tate doesn’t say whether Love was punished for his thievery or what happened to the cheese.

Presumably the attendees at Colonel Wallingford’s funeral were given gloves or rings as it was customary in the 18th century to distribute mourning gloves or rings at a funeral as mementos of the deceased. A mourning ring from the 1747 funeral of Colonel Paul Wentworth’s wife Abra is in the collections of ARCH.

A simple gold band, Abra’s funeral ring is engraved on the outside with a winged death’s head while the inside bears her name, age, and date of death. Since burials took place within a few days after a death, a local jeweler would have kept a supply of such rings on hand which could be quickly engraved with information about the deceased.

The most obvious purpose of a grave stone is to mark a person’s gravesite but it can also express the values of that person and the times during which they lived. Changing styles in grave stones reflect the changing attitudes towards death which occurred in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. A case in point is the contrast between Colonel Wallingford’s head stone and the adjacent head stone of his wife Elizabeth, who died almost 40 years later.

Colonel Wallingford’s 1771 head stone is carved with a winged death’s head surmounted by crossed bones. A verse at the bottom reads: Princes the clay must be your bed in spite of all your Powers. The tall, the wise, the Reverend head must be as low as ours. To modern eyes this all seems rather gloomy and macabre but such stones, found throughout New England, reflect Puritan concerns about death. Sometimes called “sermons in stone,” they were reminders to the living about their own mortality and what would come after death: judgment and either salvation or damnation.

Next to Colonel Wallingford’s grave is that of his widow Elizabeth, who died in 1810 at the age of 93. In the four decades between their deaths, new Protestant denominations (Methodists, Baptists, Quakers) began to take hold in New England, and the marked contrast between his head stone and hers reflects the waning influence of Puritan ideas.

Instead of a winged death’s head, Elizabeth’s head stone is carved with an urn and a willow tree. Drawn from ancient Greek and Roman architecture, the urn motif represents a memorial to the dead while the “weeping” willow expresses sadness and mourning.

Instead of a winged death’s head, Elizabeth’s head stone is carved with an urn and a willow tree. Drawn from ancient Greek and Roman architecture, the urn motif represents a memorial to the dead while the “weeping” willow expresses sadness and mourning.

The verse carved on Elizabeth’s stone, Blessed art the dead who die in the Lord, sounds less ominous and more hopeful than that on her husband’s stone. No warnings about death and damnation here! Urn and willow grave stones remained popular up to the 1850s, after which there was much greater variety in head stone styles, decorations and materials.

View our Event page to see if we have any Cemetery Tours scheduled »